A lot of “worship services” in Evangelical churches today are weak and unbiblical. They resemble rock concerts or entertainment performances in a day when many Christians are severely spiritually malnourished and lack a comprehensive Biblical worldview. These churches prioritize emotional highs, spiritual experiences, cultural relevance and a consumeristic approach to church that strays far from the God-centered reverence that Scripture demands. They lack the type of reverence we should have when we enter God’s presence. “Be not rash with your mouth, nor let your heart be hasty to utter a word before God, for God is in heaven and you are on earth. Therefore let your words be few.” (Ecclesiastes 5:2) Many church services are so casual you would think that people are going to a Starbucks and not entering the presence of the Most High.

Perhaps one of the main reasons for this is that the majority of Christians (and even pastors) cannot correctly answer the question: “What is the worship service for?” What are we supposed to be doing here? Many have not stopped to consider that God has a prescribed pattern for worship, resulting in practices that prioritize human preferences over divine commands.

This article explores the Regulative Principle of Worship (RPW) as the biblical solution. It is not just about the songs we sing (though that’s included). It insists that the whole of the corporate worship gathering must include only what God has commanded in Scripture, either explicitly or by good and necessary inference.

We’ll start by showing the dangers of abandoning the Regulative Principle, contrast it with the Normative Principle of Worship, examine how a church’s liturgy shapes discipleship, and build a compelling case for the RPW biblically, theologically, and historically. We’ll also address key objections and use examples to illustrate why many modern churches fall short—and how the RPW can restore vibrant, disciple-making worship. We’ll end with practical resources to help equip those willing to reform their worship service.

Emotionalism and Manipulation

Modern contemporary worship, with its emphasis on high-production music, atmospheric lighting, and repetitive choruses, often prioritizes emotions over biblical fidelity. Rooted in the revivalistic legacy of figures like Charles Finney (who we’ll come back to later), this approach fosters emotionalism—the pursuit of feelings as the primary indicator of spiritual vitality—and manipulation, where sensory elements are engineered to elicit responses that mimic divine encounters.

Note: the emotions are not the problem. It’s emotionalism.

Our emotions are meant to be followers but make terrible leaders. In worship, as in and all things, truth should lead our emotions.

As R.C. Sproul warns, “Emotionalism occurs when experience is sought or embraced to the exclusion or neglect of truth,” leading to an unstable faith detached from God’s Word. This not only generates a false sense of intimacy with God but also enables megachurch culture to profit from religion, perpetuating a type of consumerism that treats church as a product rather than a covenant community.

I was a part of a church that followed such a megachurch model. They had a number system to categorize songs so that they could build the emotional response in a song set. You start with a 1 (an anthem song with lots of drive), go to a 2 (something more reflective), then a 3 (a heartcry song that pulls on the heart strings) and finale with a 4 (a song with a heavy build into a climactic chorus and bridge… maybe a solo). When the preacher comes to the end of his sermon, the pads come in to “set the atmosphere” as he builds his message’s climatic alter call.

This sort of emotional charging is a not-so-subtle form of manipulation.

Add to this the repetitive, mantra-like choruses with vague lyrics (as in songs like “Build My Life”) and you have a recipe that puts people into a manipulatable state by providing emotionally moving sensory experiences that emphasize individual feelings over doctrinal depth.

These churches get “results” for sure. People come up, give, pray the prayer, etc. But, with such heavy manipulation going on—the question remains: how can you be sure it’s genuine? When I’m in tears during a song set, is it because my heart genuinely has been responding to truth, or because those chords and lights were just right?

The impact of emotionalism is reflected in the type of language you hear used by Christians in these modern worship settings:

- “When that chorus hit, I could really feel the atmosphere change. Man, that worship set got me so pumped.”

- “I was crying so much. God must have been in that place. I could really feel His presence.”

Or the types of questions they ask afterward:

- “How did you enjoy worship this week?”

Notice how centered on subjective personal experience these statements are as opposed to objective truths? Notice how absent the question “was God pleased with our offering of worship?” is from the discussion?

I’ve seen it play out so many times. It’s basically a formula now in the “church business”.

Get stellar musicians, thumping bass and drums, electric guitar solos, sing popular Christian music from the top 20 chart, get hip charismatic worship leaders, know how to use certain chords, builds, lighting, and repetition to “set the mood”, and you can very easily draw a crowd and build a vibrant big budget church that offers a ton of programs to suit its “customers” needs.

When you step back and analyze it objectively, asking why are these things being done? Is it because of some necessity from Scripture or because that’s what the people like?

The answer is obvious.

The truth is that it resembles consumer culture because it is. And churches have been reaping its rotten fruit for a number of decades now.

Now, some may at this point be tempted to think, “oh, this guy just has been burned by church and is bitter.” However, that would not be true. I sincerely love the Church. She’s Christ’s Bride. As you will see, my convictions on this topic are based on Biblical, theological and historical arguments. The aforementioned personal examples only illustrate the problem.

So, before you tune out and think that I’m just trying to be some sort of killjoy, I want you to seriously consider the issues I’m bringing up and try to objectively analyze them through the lens of Scripture and not how you feel. Try not to justify things by means of pragmatism or feelings, but by considering the Word of God on these matters.

Is every element of what you’re doing in your church’s corporate worship rooted in Scripture, or in human invention? If you have objections to my arguments, do you have a better biblical, theological and historical argument to support your position?

It is all too easy for us all to be blinded to our own traditions. Only when we are open to being challenged by another do we get the opportunity to “test all things, and hold fast to what is true.” (1 Thess. 5:21)

Manufacturing Feelings Over True Spirituality

Most Christians today don’t even have a category for considering that God may not be pleased with their worship, even though they may have thoroughly enjoyed it.

“What do you mean He’s not pleased? I thought it was great!”

Yet Scripture has something else to say (more on that to come). I’m sure that the prophets of Baal thoroughly enjoyed their worship too. I’m sure that Nadab and Abihu thought they had some great ideas for worship too!

Subjective enjoyment is not the measure of right worship.

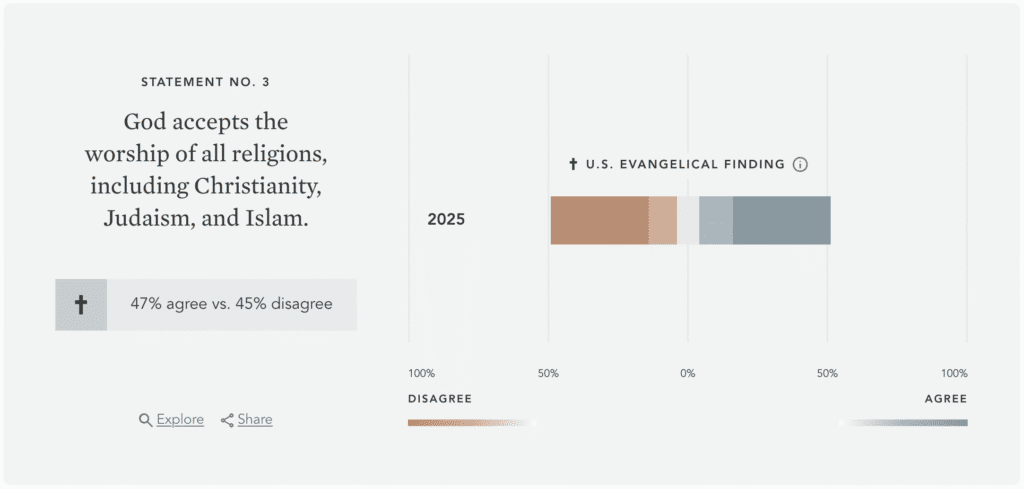

Ligonier’s State of Theology 2025 survey showed that 47% of Evangelicals thought that God accepts the worship of all religions! It’s no wonder Evangelical worship is in such a mess—apparently half of the average Christians in the pew does not even have a category for “unacceptable” worship.

Jesus warns in Matthew 7:21–23, that there will be many who “felt” close to God who hear, “I never knew you.” Such an approach risks idolatry, where worshipers idolize the experience itself.

Note also that I’m not saying that these things are necessarily done with ill-intentions. Oftentimes, people don’t know any bettter because they’ve not really thought much about it. They assume that this is just the way church is done because it’s the way we’ve always done it—at least in their memory. I want to help poke Christians to think more deeply about the corporate worship gathering instead of just going along. I want Christians to see there is a better, more biblical and historically rooted way.

Before we move on, there is one other thing we need to look at: Megachurch culture.

Megachurch Culture

Piotr J. Malysz notes, “The generic character of megachurch space… reinforces one’s focus on one’s own experience, on one’s own church consumption.”

This consumeristic approach treats attendees as customers (though they’d never outright say it), with a plethora of programs tailored to their preferences. As the Reformed Journal observes, “The church growth strategy has effectively turned the Christian parishioner into a consumerist of a spiritual experience. Everything is judged.” Churches like Bill Hybels’s Willow Creek pioneered seeker-sensitive models and commodified religion.

I don’t think that many churches realize just how significantly their own church culture has been influenced by the Megachurch, Seeker-Sensitive, and Church Growth Movements—even if they themselves aren’t a “megachurch”.

Many of the historically novel things done in the average Evangelical church today (such as Kids Ministry Programs during the main service) have no grounding in Scripture and more of a basis in pragmatism and consumeristic church models.

In Megachurch culture, the amount of people in the pews is often used to justify the means.

It’s a form of pragmatism: “But how can it be wrong? Look at how many people are coming to church! God must be blessing it.” However, by that logic, God must be blessing the Superbowl and Katy Perry concerts! Mere attendance and popularity is not the measure of faithfulness.

Furthermore, the Megachurch model perpetuates “church shopping” in the pews, where believers seek emotional fulfillment and the most programs to suit their needs. In the pulpit, it is sometimes filled with hirelings instead of true shepherds—more concerned with their own prestige and profits than truly guarding and feeding the sheep. These hired hands are often beholden to please the people rather than tell them the hard truths of Scripture that may empty pews. This can be done both by twisting God’s Word to tickle ears, or avoiding the topics that would upset their most generous givers or risk emptying the pews.1Take for example the issue of addressing the sins of women or the lies of feminism directly from the pulpit. Most preachers today wouldn’t touch that with a 10-foot pole. Other rare topics include teaching on Biblical parenting, the father’s responsibility for overseeing education and discipline of children, and gender duties in the home. Or how about talking about the false gospel of Social Justice and the farse of D.E.I. or so-called modern racial justice and woke ideology that has infected the church? How many churches help their people understand a Biblical view of the limits of government and their role in politics? During COVID we saw the immense compromise of Big Eva pastors and leaders who let a wolfish government ravish their sheep.

When the “customer” is the main focus, and the church is functionally run as a business, all sorts of compromise can be excused with pious sounding language.

However, even in churches where there may be genuine pastors who want to shepherd their flocks and feed them the Word faithfully—the dangers of emotionalism and manipulation from the modern approach to worship can still be present.

But how can even churches that have pastors who love God’s Word and are trying to be faithful inadvertently lead people astray?

The Influence of Worship Music

Even in churches committed to biblical fidelity, a subtle compromise can occur through the selection of contemporary worship music. Many congregations unwittingly support groups with aberrant, unbiblical, or even heretical theologies—such as Bethel Church and Jesus Culture, Elevation Worship, and Hillsong—by playing their songs and paying royalties through licensing services like CCLI. This financial and promotional endorsement not only funds ministries that propagate false teachings but also exposes worshipers to lyrics that can subtly shape their beliefs and practices, often more profoundly than sermons or teaching.

Through CCLI, congregations report usage and pay fees that translate into royalties for the originating churches, effectively funding their operations. For instance, Bethel Church, associated with the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR), promotes false teachings like grave soaking, prosperity gospel elements, and false signs and wonders that distort the biblical gospel. Jesus Culture, Bethel’s youth outreach, propagates similar views, including a “Jesus” who demands ongoing miracles as proof of faith, which contradicts the sufficiency of Christ’s finished work (Heb. 10:14). Elevation Worship, from Elevation Church under Steven Furtick, has been critiqued for self-promotional theology, Pelagianism, antinomianism, and prosperity gospel leanings. Hillsong Worship is linked to scandals and teachings that blend biblical truth with emotionalism and health-wealth promises. Richard P. Moore, in a Servants of Grace article, explains: “Bethel Church royalties fund and spread aberrant teaching through worship music,” noting that these funds support global outreach that draws people into false doctrines.

As Ray Burns notes, these songs are not neutral but “pipelines designed to direct people back to the main organization.”

I do not want any portion of my tithes and offerings to go to heretical churches. Almost every Christian would object if we were to say “OK, church, a small portion of your tithes are going to go to supporting the Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses.” However, all of a sudden, when it’s Bethel or Elevation or Hillsong, we make excuses because we like their tunes and they make us feel good. This is how false teaching sneaks in.

Hillsong’s former lead pastor, Brian Houston, actually wrote a book called “You Need More Money.” Elevation’s worship, led by figures like Steven Furtick, similarly prioritizes hype, with staged baptisms designed to encourage crowds through “volunteers” moving first, fostering manipulation over genuine conversion. Steven Furtick, like his heretic buddy T.D. Jakes, also appears to believe in the heresy of modalism, which teaches that God is not three persons but one being who manifests himself in different “modes.” Bethel’s Bill Johnson, teaches that Jesus had to go to hell and be tortured for three days before being born again and promotes Kenosis heresy.

These are not just minor doctrinal issues. These aren’t the types of “ministries” we should be supporting—directly or indirectly.

Leading Worship is a Teaching Role

Colossians 3:16 instructs, “Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly, teaching and admonishing one another in all wisdom, singing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs.” Note that Paul here links teaching and admonishing with the words we sing as a primary means of theological instruction and formation. When songs from problematic sources are used, they risk importing unsound doctrine, undermining the church’s commitment to truth.

Worship songs disciple believers, often shaping theology more enduringly than preaching. Worship music often shapes our theology more than preaching because melodies embed lyrics in your memory, repeating doctrines subconsciously. We’ve all been there—having a song stuck in your head.

Show me the songs a church sings, and I’ll show you the theology its people actually believe.

Scott Aniol elaborates: “The music embodies both an interpretation of the particular words of the song and an interpretation of what is actually happening in the worship service,” influencing how congregants view God, sin, and salvation.

Take for example the popular song “What a Beautiful Name” by Hillsong. It has a line, “You didn’t want heaven without us, so Jesus you brought heaven down.” This makes it seem like God was lonely in heaven without us—He so needed us. It’s very man-centered and makes the self-sufficient God out to be needy. It is an affront to the aseity of God—that He is self-existent and entirely self-sufficient, possessing fullness of being and life within Himself, lacking nothing and needing nothing. Now, there may be an orthodox way to interpret this, but given Hillsong’s tendency towards sentimental language, I doubt that was what was meant, nor is it what is often understood by congregants singing it. It’s no wonder that man-centered religion has become just as popular in the pews as in the streets.

Hopefully you see the importance of this issue now. So, let’s dive into the most important question to answer—what is the purpose of the corporate worship gathering?

What is the Primary Purpose of the Worship Service?

You cannot possibly have a fruitful discussion about how the worship service should look unless you understand it’s purpose. What is it and who is it for primarily?

Evangelism

Many people think that the worship service is primarily for evangelism. However, while evangelism may happen in a worship service—Biblically, that is not its primary purpose.

“Ascribe to Yahweh the glory due His Name; bring an offering and come before Him; worship Yahweh in the glory of His holiness.” (1 Chron. 16:29)

“Worship Yahweh with gladness; come before Him with joyful songs.” (Psa. 100:2)

“Worship the LORD your God and serve Him alone.” (Matt. 4:10)

All of these Scriptures (and more) show us that the object of worship is God. However, in evangelism, the object is man.

The Church evangelizes when its people go out from God’s presence to proclaim the Gospel to the world (Matt. 28:16—20; Acts 1:8). However, the corporate gathering is not primarily about evangelism, because its purpose is to serve believers, not unbelievers.

As Jeffrey Meyers notes,

“After all, when Paul conjectures about the presence of unbelievers in a Christian service he does not envision them being ‘comfortable’ or ‘entertained’. On the contrary, when the Church behaves properly in worship, the ‘outsider’ who enters ‘is convicted’ and ‘called to account by all’ so that ‘the secrets of his heart are disclosed, and so, falling on his face, he will worship God and declare that God is really present’ in the assembly (1 Cor. 14:24—25).”

Note that the worship service is not tailored to the unbeliever. This invalidates all “seeker-sensitive” models that put the felt needs of unbelievers as the highest priority of the Sunday service. If unbelievers visit, they will likely hear the Gospel, but it won’t be on their terms—it’ll be on God’s terms and how He desires to be revered in worship.

Note also that the effect the worship service is supposed to have on the unbeliever is that of unmistakeable conviction of sin and the holiness of God—”he is convicted by all, he is called to account by all, the secrets of his heart are disclosed”, and so, falling on his face, he will worship God and declare that God is really among you” (1 Cor. 14:24-25) and he falls down in reverent fear worshipping God. However, when was the last time you saw that response during a modern Evangelical worship service singing “Jesus is my boyfriend” style songs or trying to blunt every sharp edge of the Gospel?

Churches that put too heavy an emphasis on evangelism as the focus of their services often have sermons that all revolve around a Gospel call to repentance and faith. This is not necessarily wrong to have from time to time, but if this is the primary focus of the pulpit, it means that the sheep who are already saved are not being fed and taught the whole counsel of God (Acts 20:27)—leading to churches full of Christians with a deficient biblical worldview.

Teaching

Others believe that the primary purpose of the worship service is teaching.

So, in their minds, the sermon is the “main event” of the service. However, while teaching is an element of corporate worship, it too is not the primary focus. Moreover, the Bible’s own emphasis does not seem to be on teaching in worship (e.g. Psa. 95:1—6). Jesus himself defines His Father’s house as a “house of prayer” (Matt. 21:13; Isa. 56:7), not a lecture hall. If teaching and information exchange is the whole point of the service, then what’s wrong with just attending virtually or only tuning into the podcast? Is that doing “church”? (COVID would seem to indicate that this was what a lot of Christians thought) Yet church is so much more than just information exchange. So, while solid, faithful, Biblical exposition of the Word is very important, it too is not the whole purpose of the worship gathering.

Experience

Some others think that worship is about the experience—by which they usually mean the emotions they feel in worship. You often hear various events called a “worship experience”. However, you would be hard-pressed to prove from Scripture that this is the primary purpose of the corporate worship gathering.

In the Bible, worshippers gather to perform actions and doing things before God, not necessarily feeling things. They offer sacrifices (Psa. 4:5), they prostrate (Isa. 49:7), they confess (Psa. 32:5), they kneel (Psa. 95:6), they sing (Psa. 95:1), they bring gifts (Exo. 34:20), etc. Ironically, many of these are often removed from even conservative churches—gone are the kneeling benches of yesterday. It is totally out of sync to sing “come let us worship and bow down” standing rigidly. Even in the NT, men are commanded to “lift holy hands” while praying (1 Tim. 2:8). Postures of worship are commanded in Scripture.

Thus, worship is evaluated not based on the affect it may have on the worshipper, but rather on whether or not it was “acceptable” to God or not (see Gen. 4:3—7; Exo. 32; Isa. 1; Rom. 12:1—2; 14:17—18; Heb. 12:28—29; 13:16). The fact that God repeatedly commands our emotional responses (e.g. the repeated commands to “rejoice in the LORD” or “delight” in Him throughout Scripture), should show us that our subjective experiential feelings are not the driving focus, they are to be brought into subjection to Christ and His Word. Every one of us has struggled with our “heart not being there” for worship. However, it is not uncommon that when we do the things, the actions that God requires of us in worship, that through the help of the Spirit, our emotions follow. This is a gracious gift of God in our weakness.

Giving

The most pious sounding definition of worship is probably that “we gather for worship to give not get.” However, this is also wrong-headed. We are dependent creatures. Everything we have is from God. We are not His equals. Meyers rightly says,

Ïn fact, however, there is no such worship in the Bible for the simple fact that we cannot approach God as disinterested, self-sufficient beings. We are created beings. Dependent creatures. Beings who must continually receive both our life and redemption from God. Our ‘worship/ of God, for this reason, necessarily involves our passive reception of His gifts as well as our active thanksgiving and petitions… Our receptive posture is as ineradicable as our nature as dependent creatures. We put ourselves in a position to be served by Him… Praise follows after this and along can never be the exclusive purpose for our gathering together on the Lord’s Day.”

Hughes Oliphant Old explains,

“…God is active in our worship. When we worship God according to His Word, He is at work in the worship of the church. For Calvin, the worship of the church is a matter of divine activity rather than human creativity.”

So, while there is also giving in the corporate worship gathering, it too is not the primary purpose.

Covenant Renewal Worship

The worship service is primarily for God’s people to worship God in response to what they receive from Him.

It is the LORD’s service, not primarily because we serve Him, but rather He serves us! It is in effect, a Covenant Renewal Ceremony where God meets with us, over a shared meal, to commune with His people and remind us of His covenant with us and for us to renew our commitment to be faithful to Him. Thus, it should reflect that. This is also why the church has historically observed the Lord’s Supper as often as they met togetherm (weekly), and why the Eucharist has played such a central role in the church’s worship (even though Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox have distorted its meaning).

It is in this context that the rest of this discussion about what the corporate worship gathering should look like needs to take place.

Regulative vs Normative Principle of Worship

At the heart of worship debates are two principles: the Regulative Principle of Worship (RPW) and the Normative Principle of Worship (NPW). These approaches reflect fundamentally different views of Scripture’s authority in church services.

- The Regulative Principle of Worship holds that worship is regulated strictly by God’s Word. Only those elements commanded or implied in Scripture are permissible; anything else is forbidden, as it risks introducing human inventions that dishonor God. This principle applies specifically to corporate worship, ensuring it remains God-centered and free from idolatry.

- In contrast, the Normative Principle of Worship allows any practice not explicitly forbidden by Scripture, as long as it is edifying and promotes unity. This opens the door to innovations like dramatic performances or contemporary rituals, provided they align with general biblical principles.

The Regulative Principle of Worship was the natural outworking of the Reformed doctrine of Sola Scriptura—that God’s Word is the sole infallible and sufficient guide to life and faith—applied to the corporate gathering of the saints for worship.

This is why many of the Reformers held to it, and why many reformed churches today continue to practice it. It has a long historical pedigree which we will explore later.

The table below summarizes the key differences:

| Regulative Principle (RPW) | Normative Principle (NPW) | |

|---|---|---|

| Core Idea | Worship by only what Scripture commands or implies. | Worship using anything not explicitly forbidden, if edifying. |

| Biblical Warrant | Explicit command, approved example, or necessary inference (e.g., Deut. 12:32). | General principles (e.g., 1 Cor. 14:26 for edification). |

| Examples | Prayer, preaching, singing psalms/hymns, sacraments/ordinances | Adds elements like interpretive dance, skits or solo performances, fog machines, etc. if not sinful. |

| Risks | Restrictive, but protects from human invention and God’s displeasure. | Flexible, but risks adding unbiblical elements that are unacceptible to God. |

One of the weaknesses of the Normative approach is the simple question “by what standard?”

By what standard would you say that something like a puppet show, or fireworks, or a waterslide are not allowed in the corporate worship gathering? (And yes, those are things that some churches have done) What retort other than “it’s not our preference” or a vague appeal to “wisdom” would one have to prevent such inventions and innovations in worship? However, even for those who venture an appeal to Biblical wisdom against some excesses in worship—they’re doing the Regulative Principle… they’re just doing it inconsistently and picking and choosing when to envoke it. Without a Biblical standard, the worship gathering can become a “free-for-all”, where almost anything is permissible and able to be justified—and indeed, this is what has happened in many Evangelical churches.

Elements vs. Circumstances of Worship

One popular objection that is raised by those opposed to the Regulative Principle of Worship is, “But what about what type of chairs you use, or what time you meet, or using amplification for the sound? Scripture has nothing to say about those things, but your church does that. So, therefore, the Regulative Principle can’t be right.”

This illustrates one of the most frequently misunderstood concepts in this discussion—the distinction between the elements and circumstances of worship. The elements are the “what” of worship and the circumstances are the “how”. Elements are the essential, non-negotiable components prescribed by Scripture, while circumstances are practical details governed by wisdom and general biblical rules.

Elements: These must have direct biblical warrant and are non-negotiable to a worship service. Common examples include:

- Reading and preaching Scripture (1 Tim. 4:13; 2 Tim. 4:2)—God’s Word proclaimed forms the core.

- Prayer (1 Tim. 2:1; Phil. 4:6)—Communal petitions and thanksgivings.

- Singing psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs (Eph. 5:19; Col. 3:16)—Praising God through inspired or biblically faithful lyrics.

- Sacraments: Baptism (Matt. 28:19) and the Lord’s Supper (1 Cor. 11:23–29).

- Other occasional elements: Oaths, vows, fasting, or thanksgiving (See Westminster Confession 21.5).

Circumstances: These are incidental and flexible.

Examples include service time, seating arrangements, use of microphones, or building location, etc. These are often the incidental details necessary to fascilitate a worship service (such as a venue). These are details on which there is great flexibility and wisdom must be used to guide decisions based on context. They must not carry religious significance or become mandatory.

One of the big problems is that in many modern services, the circumstances (e.g., lighting effects) often overshadow the elements, leading to unbiblical worship. The Regulative Principle of Worship concerns the elements of worship and guards against excesses and innovations, ensuring that our worship aligns with what God has said He desires in His Word.

The so-called “worship wars” is often framed as a battle of preferences. However, my contention here is that it is not merely about preferences and tastes, it’s about what God has commanded us to do. Worship very significantly shapes the type of discipleship that occurs in a congregation.

So, next let’s briefly consider why this is so important.

How Liturgy Forms Character, Spirituality, and Theology

Liturgy—the structured order of worship—is far more than a set of rituals or traditions; it is a powerful formative practice that profoundly shapes believers’ character, spirituality, and theology. Robert S. Rayburn is right when he notes that,

“It is this disregard for the importance of what is done in the worship of God and the order or logic with which it is done that has lead to the common pejorative use of the words “liturgy” and “liturgical” in many evangelical and even Reformed circles. This is a mistake in more ways than one. Every church service is a liturgy, if it has various elements in some arrangement. That is what liturgy is. Liturgical churches are churches that have thought about those elements and their proper order. Nonliturgical churches are those that have not. It is no compliment to say that a church is a nonliturgical church. It is the same thing as saying it is a church that gives little thought to how it worships God.”

As philosopher and theologian James K.A. Smith argues in his work on cultural liturgies, humans are not primarily “thinking things” but “loving things”—creatures driven by desires and affections that are molded through repeated habits and practices. Dr. Smith describes liturgies as “formative practices” that “shape and constitute our identities by forming our most fundamental desires and our most basic attunement to the world.”2Note: I don’t endorse everything that Dr. James K.A. Smith espouses, however, I do find his general observations in his works on cultural liturgies to be insightful. In the context of Christian worship, this means that the liturgy doesn’t just express our faith; it actively trains our hearts, minds, and bodies to love God rightly. It also trains our tastes, preferences and desires.

Meyers is again insightful,

“The manner in which doctrine is embodied, communicated, lived, and sung is not neutral. Style equals form, and form matters. In other words, the form or matter in which we approach God in worship is not something indifferent (adiaphora). The way we pray and how we worship is inexorably related to who we are, to whom we are praying, and what we believer about the One we engage in prayer and praise. Style (form) and doctrine are mutually conditioning… The way in which you worship will impact what you believe.” (emphasis mine)

Thus, the form of the worship service matters. (We’ll touch more specifically on this later)

Hebrews 12:28–29 says that we are called to “offer to God acceptable worship, with reverence and awe, for our God is a consuming fire”. This verse underscores worship’s role in cultivating a holy fear and gratitude that transforms character, turning self-centered individuals into God-honoring servants.

However, when we look at the general approach to worship in many Evangelical churches, the fear of God is perhaps one of the last things on people’s minds.

People show up late, carrying their coffee cups into the sanctuary, dressed like they’re in their living rooms about to watch a movie. This should not be the attitude that a Christian approaches his LORD. Thus, the average modern worship service does not disciple people to have a healthy fear of the LORD.

The LORD’s Service

Another key Reformed insight comes from the understanding that liturgy is God’s “public service” (leitourgia) to His people, where He disciples through Word and Sacrament. Martin Luther noted that it is in the liturgical gathering that Christ “liturgizes”—gives Himself through preaching and sacraments (Luther’s Works, Sermons II, 52:39–40). This divine initiative forms character not through human effort but through God’s grace. This is also a primary reason why the corporate worship gathering must be ordered by God’s own instructions—because it is His service, not ours.

This ignorance of the worship service being part of God’s normal/ordinary means of grace is shown in the incomplete understanding of the significance of the Biblical sacraments by most Christians today. Most see them as how we express our faith to God (which it is) instead of how God puts His seal on us (baptism) and fellowships with and nourishes us (the Lord’s Supper). In both of these sacraments, there is a two-way interaction happening: God reaches out to us, and we respond to Him. One of the key insights of Reformed Theology is that God is always the primary mover—He initiates and we respond. This is true in worship and the sacraments.3I have written extensively on the historical and theological view of the Lord’s Supper and the need for reforming its practice in our churches for those interested.

How many Christians only think that the worship service is what we do for God, rather than how God serves us?

To some, that may even feel slightly blasphemous to say. However, it is what the worship service is. God comes to meet with His covenant people, and serve them, sharing a common meal with them. The LORD’s Day liturgy forms spirituality by providing a joyful foretaste of heavenly worship (Heb. 4:9; Rev. 1:10).

Candy vs Steak

Liturgy forms character by embedding godly habits into the rhythms of life. Worship “works” on a preconscious level, leveraging the things we do in it to transform our imagination and habits. This is why the form and stucture of a worship service matters—it shapes us in profound ways to a certain type of citizen who desires a certain kind of Kingdom.

When believers are trained on a diet of pop-worship songs with repetitive lyrics and crafted primarily to move them emotionally, it is shaping them. Like the influence of social media, or junk food, it alters their tastes—they get addicted to the dopamine hits of shallow but entertaining content, and the sugar rush of sweet but not particularly nourishing food. Believers trained on this sort of liturgy often will struggle to “get into theology”, finding it hard to concentrate and read or understand extended arguments.

This is not by accident. It’s because their tastes have been trained on the equivalent of spiritual candy. If they’re not entertained, they’re not interested.

Churches, even well-meaning ones, who continue to forsake the Regulative Principle in favour of modern innovations and pop-Christian songs inadvertently perpetuate this problem by continuing to shape their people in these ways. Even if their sermons are theologically rich, their worship liturgy may be unintentionally working against the maturity of their flock.

Perhaps this is one of the major reasons for the Evangelicalism’s ongoing problem of theological and biblical illiteracy, and even the lack of desire by the people to desire more depth.

If worship shapes the type of disciples we’ll be, shallow worship produces shallow disciples.

Now, to be fair—it takes work to be retrained for a Reformed worship service, because it is a meaty meal not a sugar rush. However, in Reformed worship, elements like corporate prayer, confession of sin, reciting historic creeds, singing Psalms, and the Lord’s Supper train believers in repentance, forgiveness, and communal love. Elements like the reciting of Creeds or Confessions help anchor believers to the historical church and situate them self-consciously as part of a historic faith. Singing Psalms and hymns give musical and memorable expression to deep theological truths and the full spectrum of human experience through lament, imprecation, rejoicing, repentance, sorrow, praise and awe.

This sort of retraining of tastes will be hard work, and churches who choose to reform their worship will likely lose some people in the pews. Sadly, that’s often the main reason many don’t do it.

However, the ultimate reason we should be convinced of the need for this reformation of worship is because of God’s Word. And that’s where we’ll turn now.

The Biblical Case

The Regulative Principle of Worship (RPW) is not a mere preference or historical artifact; it is a doctrine deeply embedded in the fabric of Scripture itself.

As the Second London Baptist Confession of 1689 states:

The acceptable way of worshiping the true God, is instituted by himself, and so limited by his own revealed will, that he may not be worshiped according to the imagination and devices of men, nor the suggestions of Satan, under any visible representations, or any other way not prescribed in the Holy Scriptures. (22.1)

This principle flows from God’s jealousy for His glory and His desire to protect His people from idolatry, ensuring that worship disciples believers through obedience to His revealed will rather than cultural whims or personal preferences. To build a compelling biblical case, we must examine key passages across the Old and New Testaments, showing God’s consistent demand for regulated worship. These texts demonstrate that deviations from God’s commands in worship provoke divine judgment, nullify true devotion, and fail to form mature disciples.

So this is a serious matter!

Old Testament Foundations

The Old Testament shows God’s meticulous instructions for worship and His swift punishment for innovations. These narratives and laws underscore that worship is not left to human creativity but is strictly governed by divine revelation.

- Exodus 20:3–6 (The First and Second Commandments): The Decalogue begins with commands centered on worship: “You shall have no other gods before me. You shall not make for yourself a carved image… You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I the Lord your God am a jealous God.” These verses establish God’s exclusive right to dictate how He is approached, forbidding any human-devised representations or methods. As Jeff Robinson from Founders Ministries explains, these commandments highlight that “worship of God is a primary issue, one that God takes with blood-earnest seriousness,” demanding utmost care to avoid flippancy. This sets the tone for the RPW: God regulates worship to prevent idolatry.

- Exodus 25–30 (Detailed Tabernacle Instructions): God provided exhaustive details for the tabernacle, priestly garments, and rituals, including warnings like Exodus 30:33, 38, where misuse of anointing oil or incense incurs the death penalty. This meticulousness shows God is “precise in how he ought to be worshiped,” rejecting the notion that sincerity alone suffices. This foreshadows the New Testament’s regulated worship, where elements like preaching and sacraments must similarly adhere to Scripture. God hasn’t changed—He still cares about the details of worship and we are not free to worship Him however we feel like.

- Deuteronomy 12:30–32: “Take care that you be not ensnared to follow them [nations]… and that you do not inquire about their gods, saying, ‘How did these nations serve their gods?—that I also may do the same.’… Everything that I command you, you shall be careful to do. You shall not add to it or take from it.” This passage warns against adopting worldly worship practices, commanding strict adherence to God’s revelation. It’s directly relevant to modern churches borrowing from entertainment culture, as it instructs believers to derive worship ideas solely from Scripture, not the world around them. Note also the stern warning not to add or take away from God’s instructions that regulate His worship.

- Leviticus 10:1–3: Aaron’s sons offered “unauthorized fire before the Lord, which he had not commanded them,” and fire from the Lord consumed them. God declares, “Among those who are near me I will be sanctified, and before all the people I will be glorified.” Note that the text is explicit as to why Aaron’s sons received judgment for their actions—they did that “which He [God] had not commanded them.” This exemplifies the danger of uncommanded worship, even if well-intentioned. Yet so many churches offer what the LORD has not commanded them.

- 1 Samuel 13:8–13: Saul offered a burnt offering without waiting for Samuel, leading to God’s rejection of his kingdom. Saul was presumptious to think that he could offer right worship apart from God’s designation. Saul’s disobedience in worship timing and roles, shows that even kings cannot innovate without divine warrant. We should not follow in his presumption.

- 2 Samuel 6:3–8: Uzzah touched the ark to steady it and was struck dead, despite good motives. This puts to rest the modern mantra that “attitude matters more than method.” God had given a clear instruction, it was disregarded (even perhaps with good motives), but God was not pleased because obedience is better than sacrifice (cf. 1 Samuel 15:22).

- 2 Chronicles 26:16–21: King Uzziah offered incense, a priestly role, and was struck with leprosy. This enforces worship boundaries, showing God’s judgment on unauthorized acts, a principle applicable to the lay-led innovations today.

- 2 Kings 16:10–16: Ahaz replaced God’s altar with a Damascus-style one without God’s command. Similarly, human innovations can displace divine elements, nullifying true worship—a pattern in modern churches where uncommanded extras crowd out what God has commanded.

These Old Testament examples collectively argue that God regulates worship to preserve His holiness and disciple His people in obedience, with judgments serving as sobering reminders. God has not changed. Thus, we should assume continuity, not discontinuity between the Old and New Testaments. If He has not abrogated any of these principles in the New Testament, that means that they are still in effect today.

New Testament: Spirit and Truth

The New Testament builds on the Old, applying RPW to the church age through Christ’s teaching and apostolic instruction, emphasizing worship’s Christ-centered nature.

- Matthew 15:8–9 (Mark 7:6–9): Jesus quotes Isaiah: “This people honors me with their lips, but their heart is far from me; in vain do they worship me, teaching as doctrines the commandments of men.” In context, Jesus condemns Pharisaic additions, labeling them “vain worship.” Our worship is “in vain” when we forsake God’s commandments and add human innovations instead. Dr. C. Matthew McMahon stresses this as a direct rebuke to human precepts in worship, urging churches to purge unbiblical traditions.

- John 4:23–24: “The hour is coming, and is now here, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father is seeking such people to worship him. God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth.” Here, “truth” means alignment with God’s revealed will, not cultural relevance. Note also, it is in spirit AND truth. We cannot say we’re worshipping in spirit (often an excuse for our own preferences) and divorce it from truth. Where is such truth to be found other than in God’s Word? Thus, to worship in spirit and truth is to worship according to what God has prescribed in the Bible.

- Colossians 2:20–23: Paul warns against “self-made religion” and “asceticism,” which have “an appearance of wisdom in promoting self-made religion… but are of no value.” This critiques human-invented practices that seem pious but dishonor God. We must be weary of introducing things that have an appearance of wisdom but are not commanded by God.

- 2 Timothy 3:16–17: “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable… that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work.” Scripture’s sufficiency equips us for every good work—including worship—implying that there is no need for extra sources. One of the Reformation’s primary convictions is the sufficiency of Scripture. Modern innovations in worship directly cut against this principle.

There are more Biblical passages we could explore, but I hope that the point has been clearly made that God dictates and regulates how He should be worshipped in His Word and we are not free to innovate.

The Theological Case: Rooted in Core Doctrines

In addition to the Biblical case for the Regulative Principle of Worship, there is a theological case to be made. I won’t go into detail on these, since it would make this article quite a bit longer, but just mention them here. The RPW is an outworking of foundational Reformed doctrines such as:

- The Doctrine of God and Human Finitude: God’s infinitude and our finitude mean we cannot devise worship without His revelation. As Terry Johnson asks, “How ever are we to know how to approach him?” We know because He Himself has revealed it to us.

- The Doctrine of Sin: Human hearts are “factories of idols” (Calvin), making us incompetent for devising God-honoring worship on our own. Thus, scriptural regulation helps prevent sinful inventions.

- The Doctrine of Scripture (Sola Scriptura): Scripture alone is finally authoritative source for the faith and practice of God’s people. Therefore, scripture alone can order the worship of the people of God. To say that we must turn to other sources (such as our own imaginations) to determine what we do in worship is to functionally deny the sufficiency of Scripture to equip us for every good work (2 Tim. 3:16-17).

- The Doctrine of the Church: RPW limits church power, binding consciences only to Christ’s requirements. The Westminster Confession states, “The acceptable way of worshiping the true God is instituted by Himself and so limited by his own revealed will.”

- The Doctrine of God’s Sovereignty: The RPW affirms God’s sovereign rule, asking, “What HAS God authorized?” instead of looking to man’s ingenuity or wisdom.

The Historical Case

The Regulative Principle of Worship is a historical tradition of the church. However, sadly, most of Evangelicalism has become unmoored from the historical practice of the church. Historically, adherence to RPW preserved worship’s simplicity and God-centeredness, while departures led to idolatry, superstition, and spiritual decline. As Dr. R. Scott Clark asserts, RPW “is not a novel invention of the Reformation but rather a recovery of the ancient Christian principle that worship must be according to God’s Word.” Churches neglecting RPW today stand out of step with the vast majority of Christian history, which, until the late Middle Ages, emphasized scriptural warrant over cultural accretions.

Next, we’ll briefly explore the history so that you can see this tradition and how worship got distorted today.

The Early Church: Simplicity and Scriptural Fidelity

In the apostolic and immediate post-apostolic era (c. AD 30–100), worship mirrored the synagogue model adapted through Christ, focusing on elements drawn directly from Scripture: reading God’s Word, preaching, prayer, singing psalms, baptism, and the Lord’s Supper. This simplicity aligned with RPW, as early Christians avoided pagan influences, heeding warnings like Colossians 2:8: “See to it that no one takes you captive by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition… and not according to Christ.” Hughes Oliphant Old, in The Patristic Roots of Reformed Worship, describes early worship as “a continuation of the synagogue service with the addition of the Lord’s Supper,” emphasizing lectio continua (sequential Bible reading) and psalmody. Examples include Acts 2:42, where believers “devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and the fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers,” a pattern devoid of extras like images or rituals.

When the church strayed, even subtly, consequences followed. The Didache (c. AD 50–120) warns against false prophets introducing novel practices, echoing Deuteronomy 12:32’s prohibition on additions. Early deviations, such as Gnostic influences adding mystical rites, led to heresies condemned at councils, showing how unbiblical innovations corrupted doctrine and worship.

Ante-Nicene era: Warnings Against Innovation

During the Ante-Nicene era (c. AD 100–325), church fathers like Justin Martyr, Tertullian, and Clement of Alexandria upheld worship’s scriptural purity amid persecution and pagan syncretism. Justin Martyr’s First Apology (c. AD 155) describes Sunday worship: “The memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read… then the president verbally instructs… we pray… bread and wine are brought,” with no mention of icons, vestments, or other modern additions—purely elemental and biblically derived. Tertullian (c. AD 200) in On Prescription Against Heretics insists worship must avoid “human traditions,” citing Mark 7:7–8: “In vain do they worship me, teaching as doctrines the commandments of men.” He also opposed instruments, viewing them as pagan and uncommanded elements. (Not all adherents of RPW agree with this, since Scripture itself speaks of use of instruments in worship)

Straying occurred when cultural pressures introduced innovations. For instance, some adopted mystery religion elements like elaborate baptisms, leading to Montanism’s ecstatic excesses, which Tertullian later critiqued as unbiblical. Origen (c. AD 230) warned against “self-made religion” (Col. 2:23), but his allegorism paved the way for later symbolic additions, demonstrating how deviations from scriptural regulation fostered heresy and division.

The Patristic Era: Consolidation and Early Corruptions

In the post-Nicene Patristic period (c. AD 325–500), figures like Athanasius, Basil the Great, and Augustine maintained a regulative core amid growing institutionalism. Augustine’s Confessions (c. AD 400) praises psalm singing for its scriptural edification: “How I wept, deeply moved by these hymns and canticles… the voices flowed into my ears, and the truth distilled into my heart.” He advocated simple, congregational worship, drawing from Ephesians 5:19, without endorsing images or relics. Basil (c. AD 370) emphasized worship “according to the tradition of the apostles,” rejecting novelties in On the Holy Spirit.

However, as Christianity became state-sponsored under Constantine (AD 313), innovations crept in: elaborate liturgies, clerical vestments, and veneration of martyrs’ relics. The Council of Laodicea (c. AD 364) prohibited uninspired hymns, upholding RPW-like standards, but later allowances for icons during the Iconoclastic Controversy (8th–9th centuries) marked a departure. Emperor Leo III’s iconoclasm echoed RPW by destroying images as idolatrous (Ex. 20:4–5), but the Second Council of Nicaea (AD 787) endorsed them, leading to superstition and diverting focus from Word and sacrament. This shift introduced “abuses” that the Reformation later corrected, as such additions profaned worship and weakened doctrinal purity.

The Middle Ages: Escalating Innovations and Spiritual Decline

By the Middle Ages (c. AD 500–1500), the church largely abandoned regulative simplicity, accumulating unbiblical practices that Protestants decry as corruptions. The Mass evolved into a sacrificial rite with transubstantiation (affirmed at Lateran IV, AD 1215), adding uncommanded elements like elevation of the host and indulgences (contrary to Hebrews 10:12). Relics, pilgrimages, and Marian devotions proliferated, fostering idolatry as warned in 1 Corinthians 10:14.

A prime example was the veneration of images and saints, condemned by Reformers as violating the Second Commandment. Thomas Aquinas (c. AD 1250) defended such practices via natural theology, but this led to abuses like simony and clerical corruption, sparking the Gregorian Reforms yet failing to root out innovations. R. Scott Clark highlights how medieval worship became “man-centered,” with extras like processions and chants supplanting preaching, resulting in lay ignorance and spiritual famine. The Black Death (14th century) exposed these weaknesses, as superstitious rituals offered no solace, underscoring RPW’s necessity for true comfort in God’s Word.

The Reformation: Recovery and Explicit Articulation

The Reformation (16th century) reclaimed the Regulative Principle of Worship as a return to primitive Christianity. John Calvin, in Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536), explicitly formulated it: “God disapproves of all modes of worship not expressly sanctioned by his Word… We must not seek what pleases us, but with what compliances He wills to be honored” (2.8.5; 4.10.23). Calvin stripped Geneva’s services of images, organs, and rituals, focusing on preaching, prayer, and psalms. John Knox echoed this in Scotland: “All worshipping, honoring, or service invented by the brain of man in the religion of God, without his own express commandment, is idolatry.”

Puritans further enshrined RPW in the Westminster Confession (1647): “The acceptable way of worshiping the true God is instituted by Himself and so limited by His own revealed will, that He may not be worshiped according to the imaginations and devices of men” (21.1). They abolished holy days, surplices, and kneeling at communion as unbiblical, viewing them as remnants of popery that enslaved consciences (Gal. 4:9–10). When Charles I imposed the Book of Common Prayer (1637), it sparked the Scottish National Covenant, rejecting innovations as tyrannical.

So, how did we get to where we are today if the Protestant Reformation restored the Regulative Principle?

What Happened to Modern Worship?

Modern evangelical worship did not emerge in a vacuum. It stems from a historical shift during the 19th century, particularly through the Second Great Awakening (c. 1790–1840), where revivalism supplanted true revival, leading to the rejection of the Regulative Principle of Worship (RPW).

This movement, influenced by figures like Charles Finney, abandoned historic traditions as “dead orthodoxy,” prioritizing human effort, emotionalism, and pragmatism. The result? A sub-biblical worship that manipulates feelings to produce “decisions” rather than fostering genuine discipleship through God’s prescribed means. As Iain Murray explains in Revival and Revivalism, this era marked a transition from God-centered sovereignty to man-centered techniques: “Revivalism is man working to produce an effect, while revival is God working to produce an effect.” To understand why evangelical services often resemble concerts or motivational rallies, we must trace this pernicious trajectory.

From Puritan Fidelity to Awakening Shifts

The First Great Awakening (1730s–1740s), led by Jonathan Edwards (one of my favourite theologians) and George Whitefield, maintained a strong RPW influence rooted in Puritan and Reformed traditions. Worship emphasized Scripture’s sufficiency, with preaching centered on God’s sovereignty, human depravity, and the need for divine regeneration. Revivals were seen as sovereign acts of God, not human-engineered events. Edwards, in A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God, described them as unexpected outpourings: “God has so ordered it… that the work has greatly increased ever since.”

However, the Second Great Awakening marked a departure, rejecting Calvinistic “dead orthodoxy” for Arminian emphases on free will and emotional experiences.

As Nathan Hatch notes, it “rejected the skepticism, deism, Unitarianism, and rationalism left over from the American Enlightenment,” but in doing so, it abandoned formal liturgies for spontaneous, experiential worship. Ministers like those in upstate New York dismissed traditional confessions as lifeless, favouring revivals that emphasized personal choice and immediate conversions. Collin Hansen observes: “The Great Awakenings transformed Reformation preaching into an intensely emotional experience, focused exclusively on an evangelistic message.” Events like Cane Ridge (1801), with its chaotic emotional displays—fainting, jerking, and shouting—normalized manipulation, sidelining RPW’s scriptural boundaries.

This abandonment of tradition as “dead orthodoxy” stemmed from a distrust of creeds and liturgies, viewed as barriers to “real” spirituality. As Murray recounts, revivalists equated orthodoxy with spiritual stagnation: “The older preachers responded, it’s true that to become a Christian, we all have to commit ourselves and receive Christ, but there’s a much more serious problem. By nature we are at enmity to God, and we need to be regenerated.” Yet, the Awakening’s practical Arminianism—emphasizing human ability to repent—led to a rejection of confessional standards, paving the way for innovation over regulation.

One of the key failures of the Second Great Awakening in my opinion was confusing the problem of “dead orthodoxy” with adherance to the Regulative Principle and the use of Creeds, Confessions, and other doctrinal standards. Those things were not the cause of the “dead orthodoxy” that they were reacting against. It was always, and still is, a matter of the heart.

Charles Finney: The Architect of Emotionalism and Manipulation

No figure embodies this shift more than Charles Finney (1792–1875), whose “new measures” and Pelagian theology catalyzed evangelicalism’s neglect of the Regulative Principle.

Ordained in 1824 near the Awakening’s end, Finney’s methods alarmed traditionalists but dominated by the 1830s. He denied original sin, calling it an “anti-scriptural and nonsensical dogma,” and viewed humans as morally neutral, capable of perfect obedience without divine regeneration. As Michael Horton critiques: “Finney believed that God demanded absolute perfection, but instead of that leading him to seek his perfect righteousness in Christ, he concluded that ‘full present obedience is a condition of justification.'” He rejected substitutionary atonement, stating it “assumes that the atonement was a literal payment of a debt… which does not consist with the nature of the atonement.”

Finney’s “new measures”—anxious benches (precursors to altar calls), protracted meetings, and emotional tactics like public naming of sinners—manipulated crowds for “decisions.” He declared: “A revival is not a miracle… It is a purely philosophical result of the right use of the constituted means.”

This pragmatism rejected RPW, treating worship as a tool for results: “The ‘new measures’ included… displacing the regular services with ‘protracted meetings’ (lengthy services held each night for several weeks).” Much of this influence can still be clearly seen in Pentecostalism. Murray notes Finney’s theology underpinned these: “The different methods were founded on a different theology… Finney’s position was that the will decides everything. There isn’t a fallen nature in man.”

Reformed critics like B.B. Warfield decried Finney as Pelagian, saying that in Finney’s practice, “God might be eliminated from evangelism entirely without essentially affecting its working.”

The Legacy of Finney on Modern Worship Services

As Jeffery Meyers notes in The Lord’s Service,

“Since the ill-named ‘Second Great Awakening’ in the early nineteenth century, many Protestant churches have embraced evangelistic effectiveness as teh foremost criteria for effective worship… Currently, evangelistic effectiveness drives virtually everything in ‘worship’ for many churches that identify with the ‘church growth movement'”.

This emphasis on evangelism as the primary purpose of the worship gathering shows the fundamental misunderstanding of the purpose of the corporate gathering. The worship service is not primarily for unbelievers, but rather for God’s people. However, when you look at the “seeker-sensitive” approach of many churches today, you’d never think that! This goes hand in hand with the focus on emotional responses.

Finney’s influence explains modern evangelical worship’s traits. Altar calls confuse external acts with conversion, as Bobby Jamieson observes, “Answering the call to the altar came to be confused with being converted.” Emotionalism persists in settings like Hillsong, where “music is used to create… ‘feelings of spirituality,'” manipulating via “musically driven emotions.” In the end, Pragmatism reigns and the leaders of the church growth movement claim that theology gets in the way of growth—continuing Finney’s legacy. The Second Awakening’s legacy, per Jamieson, birthed revivalism where “a ‘revival’ became synonymous with a meeting designed to promote revival.”

In sum, the Second Great Awakening, via Finney’s theology, rejected RPW as “dead orthodoxy,” birthing a man-centered worship that endures today through the Church Growth, Seeker Sensitive and Megachurch models of church. This methodology has become widespread as evident from the general structure and content of a typical Evangelical worship service. A return to scriptural regulation is much needed today.

So, what do we do and where do we start?

Recovering Psalm Singing

One of the most obvious reforms that must happen in every church today is the recovery of singing the Psalms. This should be non-debateable since it is a clear command in the New Testament.

Want to reform your worship? Sing the Psalms.

Singing psalms, as John Calvin noted in the preface to the Genevan Psalter (1542), teaches believers to pray as the Spirit intends (Rom. 8:26).

Psalm-singing was the practice of the disciples, apostles and Early Church. We really have no good reason to jettison the practice.

Jesus sang a Psalm with his disciples after the Last Supper (Matt. 26:30), and Paul and Silas likely sang Psalms in prison (Act 16:25).

Ephesians 5:19 commands believers to address “one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with your heart,” while Colossians 3:16 echoes this: “Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly, teaching and admonishing one another in all wisdom, singing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, with thankfulness in your hearts to God.”

These passages are divine imperatives for congregational singing, with “psalms” (psalmoi) referring explicitly to the biblical Psalter, ensuring that worship is saturated with God’s inspired Word rather than human compositions.

As the Westminster Shorter Catechism states that, “sin is any want of conformity unto, or transgression of, the law of God”. God has clearly commanded Psalm singing in His worship. Therefore, disregarding this is sin.

Churches neglecting Psalm singing disobey these clear commands, opting for pragmatic preferences over biblical obedience.

Note, I’m not saying that churches who do not sing Psalms are not true churches or are unfaithful in every way. But, we cannot expect God’s blessing for wilful disobedience.

I have a hard time understanding why so many pastors and church leaders push back against this. Do we think that somehow singing the Psalms is going to be detremental? As if they’re not inspired by God? NO. It’s simply that this issue, more clearly than many others, exposes the true motives behind what we do in corporate worship—whether or not it is truly based on God’s Word or man’s preferences.

So, as churches and pastors are made aware of this neglience, they should hastily take steps to correct it speedily. Neglect of Psalm singing weakens discipleship by depriving believers of Scripture’s full formative power. Recovering Psalmody restores worship’s depth, equipping saints for mature faith amid trials, emotions, and spiritual warfare.

As Keith Getty notes, much contemporary modern worship lacks depth in addressing sin, judgment, or holiness, resulting in a “de-Christianizing of God’s people.” Lyrics are frequently individualistic, repetitive, and sentimental, encouraging inward focus on feelings rather than outward praise of God’s sovereignty (e.g., mantra-like choruses that evoke emotion without doctrinal grounding). This sentimentalizes faith, omitting the raw realities of suffering, sin, and divine justice, leading to a superficial spirituality unable to sustain believers through life’s hardships.

In stark contrast, singing Psalms immerses worshipers in God’s unfiltered Word, fostering robust theology and emotional resilience. Psalms cover the full spectrum of human experience—joy, sorrow, gratitude, and anger—equipping believers to express emotions biblically (e.g. Psa. 13 for lament; Psa. 137 for an exile’s grief). They particularly enable lament, allowing honest cries to God amid pain (Ps. 88: “My soul is full of troubles”), and imprecatory prayers against oppressors (e.g. Ps. 109), teaching reliance on divine justice rather than self-pity. Modern songs rarely (if ever) include such elements, avoiding discomfort and thus failing to disciple in holistic faith. And yes, we should even sing the imprecatory psalms.

Think about it, when was the last time you heard a modern worship song about lament? Or even one that had enemies in it?

We live in times and cultures that are hostile to Christianity. The Church needs the Psalms as its battle hymns for the fight!

We must recover singing the Psalms in their fullness. Not just modern paraphrases or songs loosely based upon the more “chipper” Psalms. We must sing the whole Psalter and not pick and choose. God put each of them there for a reason, and they all are profitable for the edification of the Body of Christ.

Effeminate Worship

Much of modern worship culture exhibits an effeminate bent, with emotive, sentimental lyrics that alienate men seeking substantial engagement. Doug Wilson critiques this as “effeminate worship,” where music emphasizes “feeling worshipful” in a self-pleasing sort of way, producing “cowardly and effeminate” results in men. Services lacking references to judgment, battles, or enemies feel superficial, making men “act like women” to participate. This continues to contributes to men’s disengagement from church.

I can’t tell you how many time I’ve looked around in a modern worship service and seen men standing awkwardly there as the worship team leads the congregation in another “Jesus is my boyfriend” style song. Of course men feel awkward with that! Aside from the fact that its theologically incorrect, it’s also kinda gay for a man to sing lyrics like that. It’s no wonder most Evangelical churches are dominated by women or effeminate men and the manly men want nothing to do with it. Add to it the fact that women often lead the congregation in worship, something explicitly forbidden in Scripture (1 Cor. 14:33—35; 1 Tim. 2:12—14), and it is no wonder these churches are repulsive to men.

Psalms provide men with resonant, warrior-like language—calls to battle (Ps. 144:1: “Blessed be the Lord, my rock, who trains my hands for war”), imprecations against foes (Ps. 137:9), and triumphant praises (Ps. 149)—offering substance that aligns with biblical masculinity. Singing Psalms restores balance, drawing men into worship that equips for spiritual combat (Eph. 6:12).

Psalm Singing: A Historic Tradition

Psalm singing is no innovation but a practice from the apostles and Early Church. The New Testament church sang Psalms as part of their heritage (Acts 4:24–26 quotes Ps. 2; James 5:13 encourages singing Psalms), with early fathers like Tertullian and Augustine attesting to congregational Psalmody. Church councils like Laodicea (AD 381) affirmed Psalms’ sufficiency, prohibiting uninspired songs. Reformers like Calvin revived exclusive Psalmody, viewing it as RPW’s application, with the Genevan Psalter enabling congregational singing. Puritans and Scottish Presbyterians continued this, making it a Reformed hallmark.

Modern evangelicalism’s shift away from singing Psalms represents a downgrade, prioritizing accessibility and preferences over fidelity, leading to theological anemia.

Common Objections to Psalm Singing

Objections to Psalm singing are often pragmatic, not biblical, and can be easily refuted:

- Psalms Are Insufficient for New Testament Worship: Critics claim Psalms lack explicit gospel references. However, this shows their ignorance since Psalms prophesy Christ (Luke 24:44), covering redemption, resurrection, and the kingdom—they are sufficient as God’s Word (2 Tim. 3:16–17). Also, my position is not that of exclusive Psalmnody—simply that we should not neglect the psalms in worship (explained more below).

- Hymns Are Allowed in Eph. 5:19/Col. 3:16: The argument goes, “Hymns and spiritual songs” justify uninspired songs. This is an argument that has been often stretched beyond what the text can bear. While I will concede that one may legitimately interpret “hymns and spiritual songs” as songs not found in Scripture, there is a strong case to be made that they are actually terms that refer to categories of Psalms (e.g., “hymn” for Psalms like 145), not human compositions. The Greek terms that Paul uses are actually the same categorization of Psalms that are found in the Septuagint version of the Psalms—the same version of the Old Testament that the New Testament authors often quotes from. So, a valid way to interpret this in context is that Paul wants us to sing all categories of Psalms—the whole Psalter.

Now, I’ll note that I’m not convinced of the position of exclusive Psalmnody, since the Psalms themselves encourage us to sing a “new song” to the LORD (Psa. 96:1) and other scriptures show us new song compositions such as when Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt and when Mary sang her magnificat. However, I do have great respect for that position and I think that regardless of whether you think that hymns and spiritual songs allow for singing non-inspired songs, Psalm singing is an unavoidable command of Scripture. - Paraphrases Aren’t True Psalms: Some object that you’d have to sing the Psalms in Hebrew if you want to take it that literally since metrical versions alter wording. However, faithful metrical Psalters preserve meaning for singability, unlike loose hymns and RPW allows such circumstances. Besides, to such objectors I’d say that I this time-honoured way of doing it and trying to obey the command than their way of disregarding it and disobeying it. As much as is possible, the Psalms should be sung in a form as close to their original as possible and there are great resources that have already done this work.

- It’s Divisive or Impractical: This is really a dumb and lazy objection. Biblical obedience trumps pragmatism; start gradually to build unity. Yes, it may be difficult in the beginning, but that’s not an excuse. The truth is that learning anything in the beginning is a challenge—even catchy modern worship tunes that require click tracks.

- We Sing Psalm-inspired Songs: “We don’t directly sing the Psalms, but we sing songs that are inspired by the theology of the Psalms and songs that resemble the Psalms.” This objection is quite ridiculous when you consider it through an analogy. If I were to tell my son, “Son, please wash the dishes in the sink” and he were to come back and tell me, “dad, I rinsed the frisbee which is something resembling washing the dishes in the sink” or “I did something else inspired by the thought of washing the dishes in the sink”, I would not consider that obedience to my clear command. So, why then do we try to complicate simple obedience to a simple command of Scripture? Singing songs inspired by the Psalms is not wrong, per se. But it also is not direct obedience to the command. Lastly, we have to ask ourselves, what is the reason for such stubborn reluctance to singing the Psalms? Do we somehow think that it will not bring anything but blessing to God’s people in worship?

The question of Psalm singing in worship for me is one of the litmus tests on whether or not a church is actually willing to let Scripture regulate their worship, or if they have some other agenda taking priority. This one should be an easy point to agree to for any Christian who sees Scripture as sufficient and authoritative. However, the reluctance without any meaningful Scriptural reasoning often points to the fact that there is an unrecognized human tradition making void the commandment of God (Matt. 15:6).

Practical Ways to Implement Psalm Singing

Popular Reformed Psalters include: The Book of Psalms for Worship (Crown & Covenant), Trinity Psalter Hymnal (OPC/URC), Genevan Psalter, and Scottish Psalter (1650). There are also some wonderful modern renditions of the Psalms by The Psalms Project that doesn’t water down the language.

I’d recommend not to overcomplicate it. Pick a Psalter and start somewhere.

Introduce one Psalm monthly via preaching; use existing resources like Psallos or Brian Sauvé for accessible tunes. You can find a bunch of them on YouTube for free to get a hang of the melody (for example the Trinity Psalter and the Crown & Covenant Psalter).

There is also the awesome app website by G3 Ministries Classic Hymns that gives you sheet music, lyrics and music accompaniment with parts for a lot of Psalms and Hymns.

So, there really are no excuses for us not implementing the Psalms in our worship. There are bountiful resources even beyond what I’ve listed above that are accessible with a little effort.

If churches recover this, the blessings abound: Psalms are God’s Word, ensuring purity (Ps. 119:105); they teach doctrine (Col. 3:16); unite with saints across ages (Heb. 12:1); aid memorization for daily life; instill peace amid distress (Ps. 46); and glorify Christ as sung by Him (Matt. 26:30).

You never have to worry singing the Psalms about whether or not the words are solid because they’re Divinely inspired!

Historic Creeds, Confessions, and Catechisms in Liturgy

Another element of Reformed liturgies is the use of Creeds, Confessions and Catechisms.

Documents such as the Apostles’ Creed, Nicene Creed, Westminster Confession of Faith, Heidelberg Catechism, and others—serve not as additions to Scripture but as faithful summaries of its teachings, enabling the congregation to fulfill the scriptural mandate to declare sound doctrine collectively.

Now, some of you may be saying “aha! These things are not in the Bible. I thought the Regulative Principle only allowed what was in the Bible?” To which I’d say, “Not so fast, Bub.”

One of the first things God did when He formed His people in the OT was to give them a Creed—the Shema (Deut. 6). In the NT, the corporate recitation of creeds fits as a form of confession (Rom. 10:9–10: “If you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved”), where believers affirm biblical truths in unison. Scripture provides a clear warrant for using creeds and confessions in worship as summaries of “the pattern of sound words” (2 Tim. 1:13: “Follow the pattern of the sound words that you have heard from me, in the faith and love that are in Christ Jesus”). Paul instructs Timothy to preserve doctrinal summaries for teaching and confession. This aligns with RPW by viewing creeds as biblically derived confessions, not additions. Similarly, 2 Thessalonians 2:15 urges, “Stand firm and hold to the traditions that you were taught by us, either by our spoken word or by our letter,” referring to apostolic teachings that creeds encapsulate to guard orthodoxy.

Jude 3 exhorts believers to “contend for the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints,” implying the need for formalized statements to defend against error—creeds like the Nicene arose to combat heresies, mirroring biblical patterns (e.g., Deut. 6:4 as a creedal Shema). Under RPW, corporate recitation is an element of worship if it uses “biblical confessional materials,” as Scripture commands having a common confession.

Have you never stopped to wonder why the Early Church produced the Apostle’s Creed so early in its history and also in a time of persecution? Perhaps it was because they were obeying the teaching of the Apostles to hold fast to and pass along a pattern of sound words. The production of Creeds was born out of a need to implement Biblical commands in a practical way.

I have written more in depth about the Biblical basis for Creeds and Confessions here.